As a print designer, I realized that in every job I took, I was basically profiting off of the unsustainable lumber mill practices that causes harm to our diverse ecosystems and to our planet.

I attempted to counter this by helping clients choose recycled paper, which uses 25% less energy to make than virgin paper. Which is more important than you’d think, when you learn that the paper that ends up in our landfills emit methane.

We already know methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, and everyone attributes cow flatulence to our biggest greenhouse emissions.

But the truth is scarier: we are destroying our own air supply and leaving behind tree corpses in our wake. Human activity cuts down our planet’s main source of oxygen and replaces it with rotting paper, contributing even more to the already-existing methane—which we know is 30X more powerful in creating global warming than CO2.

The largest sources of methane emissions from human activities in the United States alone, according to the EPA, are the oil and gas system, livestock enteric fermentation, and landfills.

As a print designer, one of the only ways to make an impact for myself and my clients is by choosing recycled paper. Recycling and repurposing means lengthening its lifespan, and keeping rotting paper out of landfills.

With how much packaging and mailers are needed after (what I call) the Small Business Boom of the 2020 Pandemic, no one really knows the amount of labels, packaging, and paper waste that is actually going around. If we were to begin recycling all the paper in circulation today, how long would it take until we needed to harvest more trees?

Can we operate for the next 20, 50, or even 100 years on a paper cycle relying on 100% recycling? That idea would be unheard of today. But that’s what it’s going to take for everyone’s respective efforts to make a compound impact.

This whole “green” trend needs to stop being a trend, or a niche, or a choice (so sorry to my Cuban family who fled a life without choice).

It’s my opinion as a humble child of the Earth that our lifestyle and business practices as a society need to have “eco-friendliness” as a pre-requisite, not as an optional elective.

As humans, we need to breathe. Why do we diminish this common sense into the caricature that is the tree-hugger?

That’s because there are two types of “green” products — one is sustainable, while the other is misleading and has little to zero impact. Do you know which one you use?

“It’s expensive to be cheap,” entrepreneur Blake Sanford shares with his community. His mission to make accessible his wealth of knowledge on financial astuteness can also help point the way in the world of eco-friendliness and sustainability.

“Prime example: I had a house I was working on,” Sanford explains on his Instagram, “I ended up paying $14k for a job that could have cost me $7k.”

By entertaining subpar alternatives, the damage increased and so did the cost.

All the same, opting for these fake “green” bandwagon brands only increases the damage done to the planet. Not to mention the headache tax of choosing the product to begin with.

If consumers are already stressing about which “green” brands are trustworthy, only to find that the level of production is the same or similar to its competitors, then it gives the eco-friendly movement a bad name.

The lack of honesty from brands fuels the public divide on environmentalism.

It encourages those who were previously neutral, to start viewing eco-friendliness as a form of marketing bait — just the newest trend to buy into.

Exercising a healthy amount of discernment when it comes to the source of the product you’re purchasing is not only about looking at the ingredients, but also their values. The fortunes of the globe should not rest on the average worker, but their fortune is you.

For some brands, it is only about the money. For them, this is just another trend to sell the public the self-perception that by consuming their “green” products, you can be a good person too.

This is common sense for half the population, who understand the world of business is to get you to consume, no matter what. That’s what marketing tactics are for: to get a buyer to relate with the brand on a deeper, personal level, so they leverage the heart strings for financial gain.

The other half of the population is sourcing responsibly, working ethically, reusing and recycling whenever possible, and believing it is a global effort.

So no matter what side you’re on, we both lose.

Inauthentic expressions of environmentalism is not going to win over the hearts of Millennials (or their money), and a one-sided effort isn’t effective when it comes to the sustainability of our planet.

And still… trustworthy or not, no one really agrees on what being “green” is.

That’s because of both sides’ differing reasons to distrust the global effort.

If studying marketing tactics have taught me anything, it’s that some problems are made just to have fabricated solutions sold to people.

So maybe the idea that individual consumers need to shoulder the brunt of change is a western positivist myth propagated by the very people polluting the most. And this wouldn’t be the only instance where ethics play a huge role into how our society perceives what it means to be “eco-friendly.”

Eco-friendliness has been related to having a life of privilege due to places like Flint, Michigan infamously experiencing contaminated water due to elevated lead levels and corrosion — and it’s no coincidence that Flint is “a majority-black city where 40% of people live in poverty.”

Now, 7 years later, the water is clear but people won’t drink it.

According to Politico Magazine, “The highest-profile public-works tragedy of the past decade has triggered a bigger breakdown in trust — and carries a lesson for post-Covid America.”

Jim Ananich with his son Jake, 4, at home in Flint.

“I can’t tell somebody they should trust [claims that the water is safe],” Jim Ananich, leader of the Democratic minority in the Michigan State Senate, tells Politico, “I don’t trust them — and I have more information than most people. Science and logic would tell me that it should be OK, but people have lied to me. The anger, the lack of trust, it’s all justified.”

If people cannot trust the government to provide basic needs, or at least conduct non-corrupt audits on the systems in place that provide those needs, then how can we trust the big businesses who are slapping green labels on everything? Can we still trust the small businesses who are learning bad practices from the top, if they do the hokey-pokey and turn it all around?

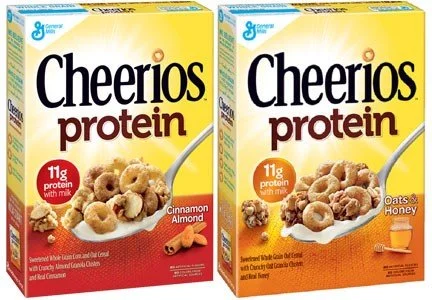

Coca-Cola Life is sweetened with cane sugar and stevia leaf extract, containing 35% fewer calories than other leading colas / Food Business News

Cheetos Protein cereal contained 16 and 17 grams of sugar compared to the original Cheerios’ 1 gram / Food Business News

Capri Sun Organic contains more calories and more sugar than its counterpart. Food Business News

When iconic brands began to experiment introducing organic products into the market, Global Consumer Strategy-Wellness director Carl Jorgensen said, many of them experienced “a swing and a miss in marketing.”

“People say they want sustainable products, but they don’t tend to buy them,” according to the Harvard Business Review, The Elusive Green Consumer.

Although the acceptance of environmentalism is growing by the year, there is still an underlying problem.

None of these brands or products that you see here are truly good for the environment. These are examples of brands leveraging the “green” movement to get you to purchase something that you might not have even thought to buy to begin with.

And therein lies the real issue.

Is it environmentally-friendly to purchase any processed goods? Is it even good for your body?

The difference becomes more clear: “Green” is not the same as “mindful.”

Creating the waste to begin with, and writing the word “green” or “organic” does not automatically make it okay. Do we need to transform how we consume and advertise? Or do consumers need to discern when they are being played by the advertising industry?

“You’re telling people to consume more in order to reduce impact,” said Rachel Kesel, founder of San Francisco group Compact who vowed to live an entire year without buying anything except food and medicine, “The more that I’m engaged in this, the more annoyed I get with things like ‘shop against climate change’ and these kind of attitudes.”

Whether the green movement is considered just a trend depends on how much impact we really see as a society. If your behaviors aren’t already detrimental to the environment, if you regularly bike to work and eat your vegetables, then going out of your way to buy goods within green-consumerism has the opposite effect.

However, if you regularly purchase plastic water bottles, virgin paper goods for things like mail packaging or toilet paper, then you have an opportunity to buy more sustainable alternatives. That’s where the real impact lies, on a case by case basis. But if people aren’t honest with each other, how can we be honest to ourselves?

“A legitimate beef that people have with green consumerism is, at the end of the day, the things causing climate change are more caused by politics and the economy than individual behavior,” said Michel Gelobter, a former professor of environmental policy at Rutgers who is now president of Redefining Progress, a nonprofit policy group that promotes sustainable living.

As New York Times author Alex Williams beautifully reported in light of the Al Gore 2006 documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, “For some, the very debate over how much difference they should try to make in their own lives is a distraction. They despair of individual consumers being responsible for saving the earth from climate change and want to see action from political leaders around the world.”

Thankfully, since then, we have seen our world leaders unite for the future and sustainability of our planet. So the amount of tone-deaf brands leveraging the “green” phase solely for capital gain are becoming more and more obvious to spot, once you know what to look for.

Just like in the good ol’ days, before privately established monetary systems, when humans would trade farmed goods for cattle and pigs, you only had one thing to protect you from the humans looking to take your resources: trust.

The ability to discern whether you can trust a stranger upon meeting them, is a skill being more forgotten the longer (and sooner) we put humans in front of screens and away from other humans.

We use this same skill to discern when product designers are just trying to use buzz words to sell you highly processed goods with bright, bold, pretty colors.

Can you tell when something is made from a machine, or made by a human?

In this growing technological society, is that a skill that will also be forgotten?

Conscious consumerism just means putting your resources back into humans, and away from mass production.

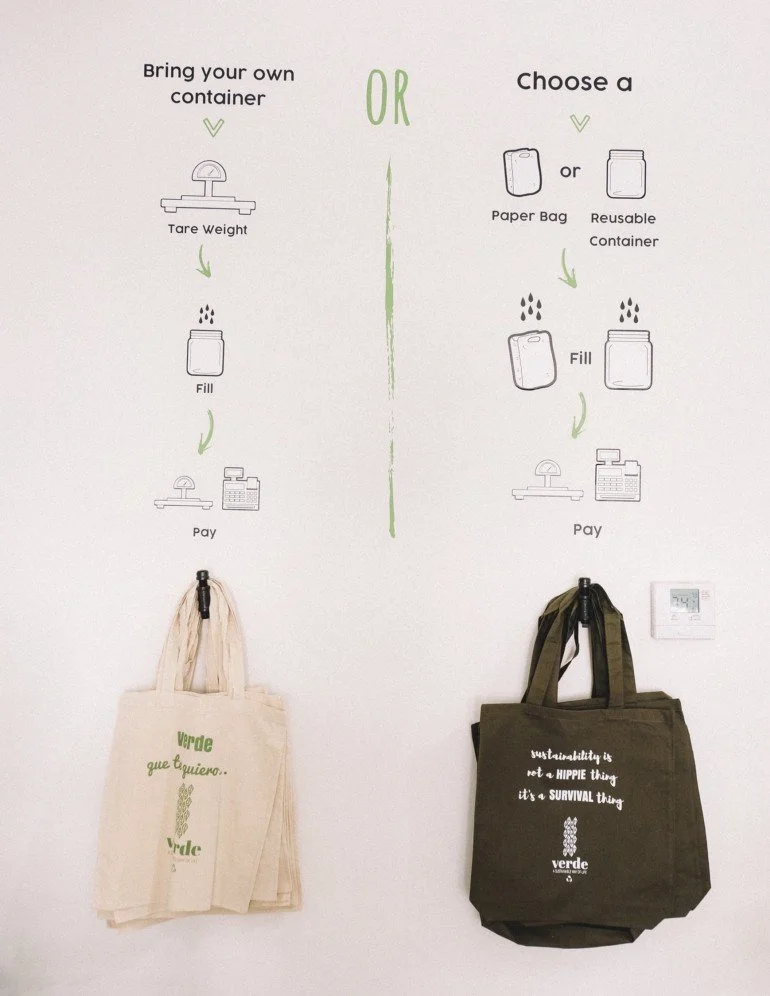

This is one Miami example of the market of the future, “complete with every needed household item from milk and laundry detergent, fresh juice, and even dog treats. The only catch is to help get customers into the habit of reusing contains, and minimizing our trash output.”

As Culture Crusaders reports, “It’s no surprise that Verde has had a warm welcome […] Their thoughtful effort to impact the lives of both their partners and their customers is immediate.”

And that’s exactly how trust should feel.

Immediate.

Sustainable, bulk-buy market: Verde on Culture Crusaders